China vs Japan: The Rivalry Reshaping Global Capital, Currencies, and Real Assets

Global markets are no longer moving in unison. The era of blanket liquidity and broad-based growth has given way to a more fragmented environment where capital is increasingly selective about risk, geography, and income reliability. After two years dominated by inflation control and aggressive tightening, the global rate cycle is turning. Inflation is easing unevenly, policy rates are beginning to fall, and the cost of capital is no longer the primary constraint it was.

At the same time, structural and geopolitical forces are reshaping where money flows. China is running one of the largest trade surpluses in history, yet faces growing difficulty redeploying capital domestically. Japan, on the other hand, is experiencing persistent currency weakness and ultra-low yields, turning it once again into a major exporter of capital. These two dynamics are unfolding simultaneously, creating capital imbalances that ripple well beyond Asia.

For investors, this shift matters. Equity markets in the United States remain crowded and expensive. Europe offers stability but limited growth. Emerging markets promise upside but carry political, currency, and execution risk. As a result, global capital is increasingly searching for a middle ground: markets that offer institutional stability, positive real yields, and exposure to tangible economic activity rather than financial narratives.

Real assets sit at the centre of this adjustment. Warehousing, logistics, housing, and infrastructure benefit directly from trade re-routing, population movement, and the physical build-out of new supply chains. Historically, these assets tend to reprice earlier than equities when rates fall, as income certainty becomes more valuable and yield spreads widen.

This month’s report explores how these forces intersect and what they mean for investors positioning for the next phase of the global cycle. Rather than focusing on a single headline risk, we examine how multiple adjustments are occurring at the same time and where they are creating durable opportunity.

This month’s edition covers:

China’s economic recalibration, capital surplus, and the constraints shaping its outbound influence

Japan’s currency pressure, yield compression, and the return of outbound investment behaviour

The rise in strategic tension between China and Japan and its implications for regional stability

How simultaneous adjustment by two economic giants is redirecting global capital flows

What this shift means for the United States, Europe, and emerging markets caught in the middle

Why real assets increasingly become the default beneficiary in a lower-rate, higher-volatility world

How New Zealand and Malaysia are positioned as complementary destinations for yield-seeking capital

1. China: Export Powerhouse, Domestic Fragility, and a Turning Point for Global Capital

China’s Strength Is Real, But It Is Narrow

China enters the current cycle with an economic profile that is increasingly polarised. On one side of the ledger, the country remains a dominant global supplier. Exports of electric vehicles, batteries, solar equipment, electronics, and industrial machinery continue to grow, pushing China’s trade surplus toward historic highs. In global manufacturing terms, China has not lost relevance. In many sectors, it has strengthened its position.

However, this strength is highly concentrated. Export momentum is being driven by a relatively narrow band of industries that benefit from scale, state support, and global cost competitiveness. Outside these sectors, domestic activity tells a very different story. Retail sales growth remains uneven, private investment is cautious, and household confidence has yet to recover meaningfully from the property downturn of recent years.

This creates a paradox. China looks powerful when viewed through the lens of trade data, but internally it is operating below potential. That imbalance is shaping how capital moves both within China and beyond its borders.

Domestic Demand: The Missing Engine

The core challenge facing China today is not production capacity, but demand. Property, which once acted as the primary store of household wealth and a key driver of local government revenue, has yet to stabilise in a way that restores confidence. While policymakers have rolled out incremental support measures, they have deliberately avoided a large-scale rescue that would re-inflate leverage.

At the same time, households remain cautious. Savings rates are elevated, discretionary spending is restrained, and younger demographics face a more competitive labour market than previous generations. Businesses, particularly in the private sector, are responding by conserving cash rather than expanding aggressively.

The result is an economy that produces more than it consumes. That excess must go somewhere, and increasingly it is flowing outward through exports, overseas investment, and regional expansion.

Policy Direction: Support, Not Stimulus

Beijing’s policy stance reflects this reality. Rather than launching a broad stimulus wave, authorities have focused on targeted measures: trade-in subsidies to encourage consumption, support for advanced manufacturing, and incentives tied to technology and energy transition. These steps are designed to stabilise growth without reigniting the excesses of the previous cycle.

What is notable is what policymakers are not doing. They are not engineering a property-led recovery. They are not flooding the system with unrestricted credit. Instead, they appear willing to tolerate slower headline growth in exchange for structural rebalancing.

This matters for global markets. A China that is stable but not booming behaves very differently from a China in full stimulus mode. It exports goods and capital rather than absorbing them.

Capital Seeking an Outlet

As domestic opportunities deliver lower marginal returns, Chinese capital has become more outward-looking. This is visible in rising outbound investment, regional infrastructure engagement, and growing interest in overseas real assets. Capital is not fleeing China in panic. It is being redeployed in search of yield, diversification, and regulatory certainty.

This shift coincides with increasing geopolitical friction and trade scrutiny from developed markets. Restrictions on technology transfer, supply-chain resilience policies, and strategic alignment among US allies have narrowed some traditional channels for Chinese firms. In response, capital has become more selective, favouring markets that offer neutrality, rule of law, and long-term income stability.

Why This Sets the Stage for Japan

China’s position is important not in isolation, but in contrast to Japan. As China runs large external surpluses while managing internal constraints, Japan faces the opposite dynamic: domestic stability paired with external currency pressure. Together, these forces are reshaping how capital moves across Asia.

China’s export strength and demand shortfall create outward pressure. Japan’s weak currency creates a powerful funding mechanism. The interaction between these two economies is no longer just a trade story. It is becoming a capital-flow story, with implications that reach well beyond their borders.

This is the backdrop against which the Japan–China dynamic must be understood. One side is exporting goods and capital. The other is exporting capital through currency weakness. The next section examines how Japan’s yen has become one of the most important financial signals in the global system today.

2. Japan: The Yen Crisis, Strategic Friction, and the Return of Capital Export

The Yen Is Weak for Structural Reasons

Japan’s currency weakness is no longer a short-term anomaly. The yen has remained under sustained pressure even as global inflation has cooled and rate expectations have begun to shift elsewhere. While headline narratives often frame this as a temporary divergence driven by US interest rates, the reality is deeper and more structural.

Japan remains the last major economy still operating under ultra-accommodative monetary conditions. The Bank of Japan has adjusted its yield curve control framework, but policy remains highly supportive compared to the United States and Europe. This persistent rate differential continues to encourage capital outflows, particularly from institutions and corporates seeking higher returns abroad.

At the same time, Japan’s demographic reality limits the scope for aggressive tightening. An ageing population, a shrinking workforce, and subdued domestic consumption mean that policy makers are cautious about moves that could destabilise growth. The result is a currency that absorbs pressure rather than resisting it.

The yen’s weakness, therefore, is not just about global rates. It reflects Japan’s role as a structural funding market in the global system.

A Weak Yen Changes Behaviour

Historically, prolonged yen weakness has triggered a predictable response. Japanese capital moves outward. This occurs across multiple channels: corporate overseas expansion, institutional portfolio allocation, and private capital seeking yield.

For Japanese investors, the logic is straightforward. When domestic yields are low and the currency is weak, overseas assets offer both income and diversification. Even modest yields abroad can translate into attractive real returns when funded in yen. This dynamic has played out repeatedly over past decades, and the current environment closely resembles earlier episodes of outward capital deployment.

What is different this time is scale. Japan remains one of the largest pools of savings in the world. Pension funds, insurers, and corporates hold substantial capital, and the incentive to deploy it externally is strengthening rather than fading.

In practical terms, Japan is becoming a low-cost funding source again. Capital raised or redeployed from Japan is finding its way into infrastructure, property, and private credit across Asia-Pacific and beyond.

Strategic Tension with China Adds Volatility

Overlaying this financial dynamic is a more complex geopolitical relationship with China. Economic ties between the two countries remain deep, but strategic friction has increased. Supply-chain realignment, technology controls, and regional security considerations have added a layer of uncertainty to cross-border investment decisions.

For Japanese corporates, this has accelerated diversification away from over-reliance on China-based production and revenue. Southeast Asia, Australia, and select neutral markets have become preferred alternatives. The objective is not disengagement, but resilience.

Financial markets are sensitive to this shift. Periodic flare-ups in political or trade-related tensions tend to amplify currency volatility and reinforce capital outflows from Japan. Each episode strengthens the perception that holding excess domestic exposure carries opportunity cost.

From Currency Weakness to Capital Export

Taken together, these forces have repositioned Japan within the global capital cycle. The country is no longer viewed primarily as a destination for yield. It is increasingly seen as a source of funding for yield elsewhere.

This has direct implications for real assets. Japanese capital has a long history of targeting property, infrastructure, and long-duration income assets offshore. These investments are typically conservative, yield-focused, and structured for long-term holds. They favour markets with legal certainty, transparent ownership structures, and stable income streams.

As the yen remains under pressure, this outward flow is likely to persist. Even if global rates ease, Japan’s relative position means it will remain one of the cheapest funding currencies in the developed world.

Matters Beyond Japan

Japan’s role as a capital exporter does not exist in isolation. It intersects directly with the situation in China and with broader global conditions. While China is exporting goods and seeking external outlets for excess capacity, Japan is exporting capital driven by currency dynamics and yield differentials.

This combination creates a powerful regional effect. Capital looks for places where demand is real, income is stable, and geopolitical risk is manageable. It is in this gap that countries like New Zealand and Malaysia become relevant.

The next section brings these threads together. When China’s export-driven surplus meets Japan’s capital export cycle, the result is not abstract macro theory. It is tangible pressure on asset markets, particularly in real estate sectors tied to logistics, infrastructure, and workforce accommodation.

Understanding this interaction is essential to positioning portfolios for the next phase of the cycle.

3. Rising Strategic Tensions Between China and Japan

Why This Matters for Markets, Trade, and Capital Flows

Relations between China and Japan have long been characterised by deep economic interdependence alongside recurring diplomatic and security friction. In 2025, that balance has shifted. What was once a managed rivalry is increasingly taking on the characteristics of a strategic confrontation, with direct implications for trade, currencies, investor confidence, and regional supply chains.

This shift matters because China and Japan are not peripheral economies. They sit at the core of Asian manufacturing, global shipping routes, and cross border capital flows. When tensions rise between them, the effects travel well beyond bilateral politics.

Diplomatic Fractures Are Becoming Harder to Contain

Recent months have seen a marked deterioration in diplomatic tone. Statements by senior Japanese officials linking regional security risks to Taiwan have drawn sharp responses from Beijing, which views such comments as a challenge to long-standing diplomatic understandings. Efforts to clarify or soften language have not fully eased tensions, highlighting how sensitive and reactive the relationship has become.

At the same time, historical memory continues to influence present day diplomacy. Commemorations of wartime events have taken on a more nationalistic tone, reinforcing domestic political narratives on both sides. These dynamics make compromise more difficult and raise the likelihood that disputes escalate rather than fade quietly.

China has also demonstrated a willingness to use targeted diplomatic pressure, including restrictions on individuals and symbolic measures aimed at signalling displeasure. While these steps may appear limited, they contribute to a broader atmosphere of mistrust that affects economic engagement.

Economic Channels Are Already Feeling the Impact

Political strain is increasingly spilling into economic behaviour. Chinese authorities have issued guidance cautioning citizens about travel to Japan, which has coincided with a noticeable drop in visitor numbers. This has had immediate effects on tourism dependent cities and businesses, reminding markets how quickly diplomatic tensions can translate into real economic cost.

Beyond tourism, cultural exchanges and business delegations have slowed. Informal ties that once supported investment and trade are being tested. Even symbolic gestures that previously served as stabilising elements in the relationship have become more fragile, reinforcing the sense that the relationship is cooling rather than stabilising.

For investors, these developments highlight an important risk. Economic exposure between China and Japan remains significant, but political willingness to insulate commerce from diplomacy is weakening. That raises uncertainty around sectors that depend on smooth cross border interaction.

Security Tensions Are Becoming More Visible

Alongside diplomatic strain, military signalling has increased. A series of close encounters in regional airspace has underscored how quickly routine patrols can become flashpoints. These incidents may not escalate immediately, but they heighten risk perception and reinforce the sense that strategic competition is intensifying.

Joint military activity involving China and its partners near Japan has prompted corresponding responses from Japan and its allies. Exercises and air patrols are increasingly framed as demonstrations of readiness and deterrence rather than routine operations. This visibility matters because it shapes how businesses, insurers, and investors price geopolitical risk in the region.

The presence of external powers further complicates the picture. Strategic alliances and security commitments mean that bilateral tensions do not remain contained. They become embedded in a wider regional security framework that amplifies uncertainty.

Taiwan Remains the Central Fault Line

At the core of rising tension is Taiwan. Japan’s evolving public stance on regional security has unsettled Beijing, which views any shift in language or emphasis as a challenge to established diplomatic foundations. Efforts by Japanese officials to manage messaging have not fully reassured China, particularly as regional military activity around the Taiwan Strait continues.

For markets, Taiwan is not just a political issue. It is a node in global supply chains, particularly in semiconductors and advanced manufacturing. Any deterioration in stability around the Strait raises the risk premium for firms operating across East Asia and encourages diversification away from concentrated exposure.

What This Means for Capital and Investment

Strategic tension alters behaviour even when fundamentals remain strong. Companies reassess where they deploy capital. Investors demand higher returns to compensate for political risk. Supply chains are redesigned not just for efficiency but for resilience.

In this environment, capital increasingly looks for jurisdictions that offer stability, neutrality, and dependable returns. This is where secondary markets and real assets gain relative appeal. When political risk rises between major powers, investment does not disappear. It reallocates.

For real asset investors, the China Japan dynamic reinforces a broader theme of this cycle. Geopolitical friction at the core of the global economy strengthens the case for income backed assets in stable jurisdictions. Yield becomes a buffer against uncertainty, and physical assets provide grounding when financial markets are driven by sentiment and strategic risk.

4. When Two Giants Adjust at the Same Time: The Capital Flow Consequences No One Talks About

China is framed as a demand problem. Japan is framed as a currency problem. But the more investable insight is what happens when both adjust at the same time.

When two of the world’s largest capital pools face constraints at home, the pressure does not disappear. It relocates. The effect shows up first in cross border capital flows, then in real assets, and only later in listed markets.

China’s Capital Surplus Has Fewer Places to Go at Home

China continues to generate large external surpluses through trade and industrial production. In simple terms, the system still produces more export earnings than it can easily recycle domestically into high returning projects.

That is not because China lacks capital. It is because domestic deployment has become more difficult. Property no longer absorbs national savings the way it once did. Household confidence remains cautious. Local government funding channels are constrained. Private sector investment is selective. Even when stimulus is applied, it tends to stabilise rather than reignite the previous cycle.

This creates a familiar condition in global macro. Excess capital that cannot find attractive domestic deployment looks outward, either directly through investment, or indirectly through supply chain relocation, outbound corporate expansion, and increased overseas asset exposure by institutions and wealthy families.

Japan’s Outbound Capital Is Becoming Structural Again

Japan’s mechanism is different but the outcome is similar. The yen remains weak relative to global alternatives, and domestic yields remain low. That combination makes Japan a cheap funding base and encourages capital to seek return elsewhere.

It is not simply a story of speculation. It is also institutional behaviour. When local returns are compressed, large pools of capital tend to diversify internationally, especially into assets that offer stable income and high certainty of cash flow.

Two Different Motivations, One Shared Direction

This is the key point. China and Japan are both incentivised to invest overseas, but for different reasons.

China is pushed outward by excess capital and limited domestic absorption. Japan is pulled outward by low yields and a weak currency. One is about deployment. The other is about return.

When these two forces operate at the same time, the downstream effect is a broad bid for stable real economy assets outside their borders. Not everywhere benefits equally. Capital tends to flow toward regions that offer three things: scalability, stability, and investable infrastructure.

Where the Capital Goes First: The Global Absorbers

Southeast Asia is increasingly the absorber of industrial redeployment. As supply chains diversify, the region captures manufacturing, logistics, industrial land demand, and the supporting labour and housing ecosystem that comes with it. This is not only about factories. It is about the entire corridor infrastructure that makes production and distribution possible.

Oceania plays a different role. It absorbs capital seeking stability, yield, and rule of law. It benefits from being boring in the best way. When investors want predictable outcomes, transparent systems, and defensible income, this is where allocations increase. That tends to show up in high quality industrial, logistics, managed residential, and long duration infrastructure linked property.

Why Real Assets React Before Equities

Equities respond to narratives and expectations. Real assets respond to cash flow, land constraints, and real activity.

When cross border capital begins to reposition, it often shows up earlier in physical markets than in public markets. Warehousing demand increases before listed logistics names re rate. Rental competition tightens before REIT valuations reprice. Serviced housing occupancy rises before residential sentiment turns.

This is why real estate becomes the first transmission channel for this adjustment. It provides income and security at the same time, and it is harder to arbitrage away than a public stock trade.

What This Means for Investors

The practical takeaway is that the next cycle may be driven less by domestic growth stories and more by international capital behaviour.

When China and Japan both lean outward at the same time, the beneficiaries tend to be markets that offer stable yield, real utility, and policy credibility. For real asset investors, that matters more than short term headlines.

This is the context for why New Zealand and Malaysia can sit in the path of the same flow, but for different reasons. One offers stability and yield in a lower rate environment. The other offers growth corridors being pulled into regional infrastructure demand.

That is the bridge into the next section, where we translate these macro forces into the specific levers investors should watch and the asset types most exposed to this repositioning.

5. The World Economy Caught in the Middle

What This Means for the US, Europe, and Emerging Markets

As China and Japan adjust at the same time, the consequences do not stay confined to East Asia. They ripple outward into global capital markets, trade flows, and investment decision-making. The world economy is entering a phase where the traditional “safe” destinations and the traditional “growth” destinations both look less straightforward than they once did.

This is creating a rare moment where global capital is not chasing extremes. Instead, it is reassessing the balance between risk, yield, and durability across regions.

The United States: Expensive Stability, Narrow Leadership

The United States remains the centre of global capital markets. Its financial system is deep, liquid, and structurally dominant. When uncertainty rises elsewhere, capital still gravitates toward US assets almost by reflex.

However, the nature of that stability has changed.

US equity markets are increasingly concentrated. A small group of large technology and AI-linked companies now account for a disproportionate share of index performance, capital inflows, and investor optimism. Outside of these names, earnings growth has been far more uneven. Valuations, particularly for high-quality assets, reflect expectations that are already stretched well into the future.

At the same time, US interest rates, while expected to decline, remain higher than in most developed economies. This has supported the dollar but has also raised the hurdle rate for new investment. For global investors, US assets now offer safety and liquidity, but less margin for error. Returns increasingly depend on continued multiple expansion rather than income or broad-based growth.

The US is not unattractive. It is crowded. And crowded markets tend to behave differently when conditions change.

Europe: Institutional Safety, Structural Limits

Europe occupies a different position. Its appeal is rooted in institutions rather than momentum.

Strong regulatory frameworks, established infrastructure, and conservative banking systems give European markets a sense of resilience. During periods of stress, European assets are often viewed as capital-preservation vehicles rather than growth engines.

Yet Europe faces long-standing structural challenges. Demographics are unfavourable. Productivity growth has lagged other regions for years. Fiscal flexibility is limited by political fragmentation and high debt levels in several member states. Energy security, while improved since 2022, remains a long-term constraint on industrial competitiveness.

For investors, this creates a trade-off. Europe offers lower volatility, but also limited upside. Capital flows into the region tend to be defensive in nature. They seek stability, not expansion. In a world where capital is increasingly mobile and return-sensitive, that limits Europe’s role as a primary destination for incremental global investment.

Emerging Markets: Growth With Friction

Emerging markets present the opposite challenge. Growth potential remains significant, driven by demographics, urbanisation, and industrial expansion. Southeast Asia, India, parts of Latin America, and selected frontier markets continue to attract manufacturing and infrastructure investment.

However, growth in emerging markets often comes with friction. Political risk, regulatory unpredictability, and currency volatility complicate long-term capital deployment. Even when underlying demand is strong, returns can be eroded by exchange-rate movements or policy shifts that sit outside investor control.

In periods of global uncertainty, these risks become harder to justify. Capital does not disappear from emerging markets, but it becomes more selective. Investors favour assets with shorter payback periods, hard-currency income, or strategic importance, while avoiding broad exposure to domestic cycles.

This is why, despite strong growth narratives, many emerging markets struggle to capture large pools of institutional capital during transitional phases of the global cycle.

The Result: Capital Searches for the Middle Ground

When the US is expensive, Europe is slow, and emerging markets are volatile, capital does not stop moving. It recalibrates.

What global investors increasingly seek is a middle ground. Not the highest growth, and not the lowest risk, but the most balanced combination of the two.

This middle ground is defined by several characteristics:

Stable governance and legal frameworks that protect capital

Moderate, predictable growth rather than boom-and-bust cycles

Positive real yields that compensate for inflation and currency risk

Visible infrastructure demand that anchors long-term cash flow

Countries and regions that meet these criteria become disproportionately attractive during periods of global adjustment. They absorb capital not because they are fashionable, but because they are functional.

This is the context in which global capital flows should now be understood. The world economy is not collapsing, nor is it entering a uniform expansion. It is fragmenting into zones of different risk and return profiles. And capital, by nature, flows toward where balance is most achievable.

This sets up the next question naturally:

If capital is looking for balance rather than extremes, which asset classes are best positioned to receive it?

That is where real assets come back into focus.

6. Why Real Assets Become the Default Winner

Yield, Stability, and Repricing Power

When global capital enters a transition phase, history shows that it does not move randomly. It follows a familiar sequence. Financial assets tend to react first. Real assets follow later, but more persistently. This pattern has repeated across multiple cycles, and the current environment fits the same structural conditions.

The core reason is simple. Real assets sit beneath financial narratives. They respond to cash flow, cost of capital, and physical demand, not sentiment alone.

Falling Rates Change the Rules of Allocation

Periods of global rate cuts consistently alter investor behaviour. When policy rates fall, the opportunity cost of holding income assets declines. This does not automatically create speculative excess. Instead, it raises the relative value of stable yield.

Historically, major easing cycles have shifted capital away from cash and low-growth bonds toward assets that can deliver income with some inflation protection. In the early 2000s, following the post-dot-com easing cycle, real estate and infrastructure significantly outperformed broad equities. A similar pattern emerged after the Global Financial Crisis, where assets offering contractual income re-rated steadily as rates remained low for an extended period.

What matters is not the first rate cut, but the signal it sends. Once central banks move from fighting inflation to supporting growth, the market begins to price a longer period of lower funding costs. That is when income-producing assets gain repricing power.

Currency Volatility Pushes Investors Toward Income Certainty

Another recurring feature of late-cycle transitions is currency instability. When interest rate differentials narrow and capital moves across borders, exchange rates tend to become more volatile.

In such environments, investors place greater emphasis on income certainty. Assets that generate cash flow in local terms, especially where inflation is moderate, become anchors in portfolios. This is particularly true for cross-border investors, who often accept some currency risk if the underlying yield is sufficient to absorb volatility.

Real assets have historically filled this role. Long-leased industrial properties, residential assets with stable occupancy, and infrastructure-linked facilities provide income that is less sensitive to market sentiment than equity dividends. This is why pension funds, sovereign investors, and insurance capital consistently increase real asset allocations during periods of macro adjustment.

Physical Assets Absorb Structural Change Before Markets Reprice It

There is also a timing element that favours real assets.

Structural shifts in the economy show up first in physical demand. Trade rerouting increases warehouse utilisation before it lifts equity earnings. Population movement tightens rental markets before it changes national growth forecasts. Infrastructure investment consumes land and power capacity years before it fully appears in GDP data.

This lag matters. By the time financial markets fully price structural change, real assets tied to that change are often already producing higher income. The repricing happens quietly through rent growth, lower vacancies, and improving covenant strength, not through headlines.

This is particularly evident in logistics, industrial, and housing markets linked to employment and infrastructure. These sectors respond directly to real activity rather than expectations.

Evidence From Past Cycles

The idea that real assets outperform during transition periods is not theoretical.

In the mid-2000s, global trade expansion drove strong performance in logistics and industrial real estate well before equity markets recognised the scale of supply-chain transformation. After the Global Financial Crisis, income-producing property and infrastructure assets delivered some of the strongest risk-adjusted returns as rates stayed low and volatility remained elevated.

Even during more recent shocks, such as the pandemic period, assets with physical utility and stable demand recovered faster than many growth-oriented financial assets. Warehousing, residential rental stock, and essential infrastructure demonstrated resilience precisely because they were anchored to real-world usage.

Why This Cycle Follows the Same Logic

The current cycle combines several of these historical drivers at once. Global rates are shifting lower. Currency volatility is rising. Trade patterns are adjusting. Capital is becoming more selective.

At the same time, financial markets are increasingly concentrated and sensitive to shifts in sentiment. This increases the relative appeal of assets that do not rely on narrative continuation to deliver returns.

Real assets benefit not because they are immune to cycles, but because their return drivers are simpler. Income is paid today. Demand is visible. Costs and constraints can be measured.

That is why, as global capital searches for balance, real assets often become the default winner. Not as a speculative play, but as a stabilising allocation that can absorb structural change while continuing to generate cash flow.

The final step is understanding where this dynamic is most visible today. Not all markets offer the same combination of yield, stability, and structural demand.

That brings the focus naturally to New Zealand and Malaysia.

7. New Zealand and Malaysia as Capital Magnets in This Cycle

New Zealand: Yield Stability With Policy Support Now in Motion

New Zealand is entering the next phase of the cycle from a position income investors tend to favour. Monetary tightening has already done its work, inflation pressure has moderated, and policy has clearly pivoted toward growth support. This matters because real assets typically begin to reprice when the cost of capital falls faster than income does.

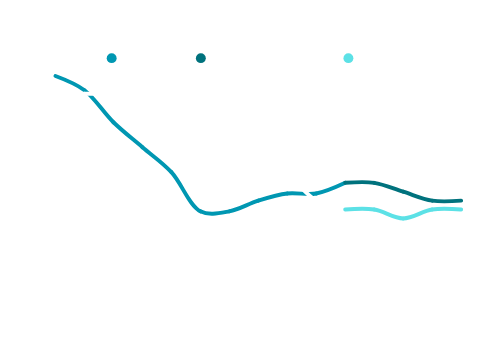

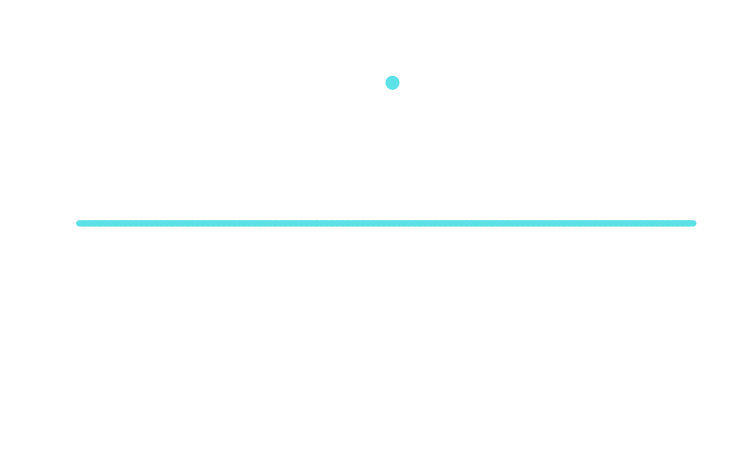

As shown in the CPI versus OCR chart, headline inflation has cooled substantially from its 2022–2023 peak. By Q3 2025, CPI has eased toward the low-3 percent range, while the Official Cash Rate has already been reduced to 2.25 percent. With projected inflation trending lower into 2026 and policy rates stabilising in the low twos, real interest rates are no longer restrictive. This is the environment in which yield assets regain relevance.

The implication for property is not an immediate boom, but a gradual re-rating of income. When borrowing costs compress toward income yields, investors are paid to hold assets through a slow recovery rather than relying on rapid capital appreciation.

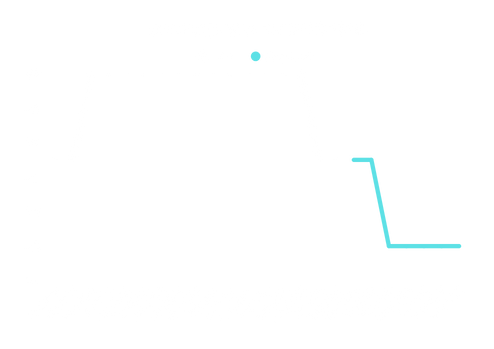

The housing and construction data reinforces this setup. The consents chart by dwelling type shows a clear downshift in new supply from the 2021–2022 peak. Stand-alone houses, apartments, and retirement village units have all seen materially lower volumes through 2024 and 2025.

This is not a demand collapse. It is a supply response to higher funding costs, margin pressure, and development risk. Historically, this pattern precedes firmer rents and stronger occupancy before it lifts prices, particularly once monetary conditions begin to ease.

On pricing, national housing indicators suggest stabilisation rather than renewed decline. Transaction volumes remain measured, but the pace of softening has slowed, and price movements are increasingly flat rather than negative. This is consistent with the early stage of a yield-led recovery rather than a speculative rebound.

Currency adds another layer to the investment case. The NZD remains weak relative to its long-term average, effectively lowering the entry cost for offshore capital. If the currency stays soft while domestic rates ease, foreign investors are acquiring New Zealand income streams at a discount, with potential currency upside over a medium-term horizon.

Taken together, the data points to a market where downside risk has narrowed, yield is doing more of the work, and policy conditions are becoming progressively more supportive. New Zealand’s appeal in this cycle is not acceleration, but stability with re-rating optionality.

Malaysia: Yield Premium Plus Currency Strength in a Supportive Policy Setting

Malaysia plays a different role in the global capital map, but the attraction is equally compelling. The key shift is that policy is no longer just neutral. It is now mildly supportive.

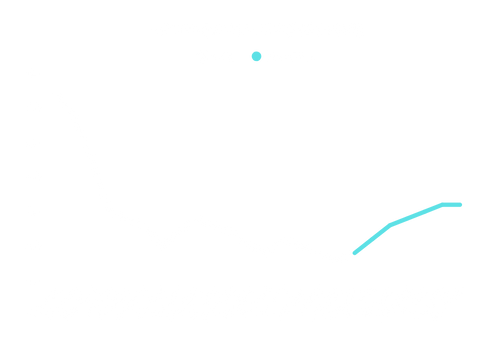

The OPR chart shows Bank Negara Malaysia’s pivot in July 2025, when the policy rate was cut by 25 basis points to 2.75 percent after more than two years on hold. Since then, the central bank has maintained a steady stance, signalling comfort with current conditions while retaining flexibility if external risks intensify.

This shift matters for real assets. Lower policy rates reduce hurdle rates without undermining financial stability.

Inflation dynamics support this policy stance. As shown in the CPI chart, Malaysian inflation has cooled steadily through 2024 and 2025, settling in the low-to-mid 1 percent range. This creates a positive real yield environment without forcing restrictive monetary settings.

For investors, this combination is powerful. Property income yields remain well above inflation and borrowing costs, preserving a wide margin of safety.

Currency conditions further strengthen Malaysia’s positioning. Unlike many emerging-market peers, the ringgit has shown relative resilience and signs of recovery. This reduces FX anxiety around income streams and reframes Malaysia as a quality yield market rather than a pure risk trade.

Structurally, Malaysia continues to absorb real economic activity. Manufacturing, logistics, and trade throughput form the base layer of demand. AI and data-centre investments then act as accelerants, particularly in Johor and Klang-linked corridors, but they are building on an already active industrial ecosystem rather than creating demand in isolation.

Prime industrial and logistics assets continue to trade at yields materially higher than those in Singapore and other developed markets. With inflation contained and policy no longer tightening, that yield premium becomes increasingly attractive to global capital.

The Fairhaven View

Across both markets, the charts tell a consistent story. Policy pressure has eased, inflation is no longer the binding constraint, supply is tightening in key real asset segments, and currency dynamics are supportive rather than hostile.

New Zealand and Malaysia sit in the middle ground global capital is increasingly seeking. They offer stable governance, positive real yields, and exposure to tangible economic activity rather than crowded financial narratives.

This is not a call for speculative risk-taking. It is a case for disciplined positioning in markets where income is reliable, policy is predictable, and valuation adjustment is driven by fundamentals.

8. Featured Listings: Different Roles, Same Capital Magnetism

New Zealand: Stabilised Yield in a Lower-Rate Environment

East Tamaki – High-Spec Logistics Facility

Asking Price: NZD 55 million

Asset Type: Industrial | Modern warehouse and office with large canopy

Land Size: Prime industrial zoned parcel (exact site area undisclosed, typical for precinct)

Built-Up Area: ~100,000 sq ft

Nearby Demand Drivers: SH1 access, Port of Auckland, Auckland Airport, Wiri Inland Port, East Tamaki industrial cluster

Notes:

East Tamaki is one of the most liquid and competitive industrial markets in the country. This asset’s configuration is ideal for high-turnover logistics operations, including hardware staging, cloud equipment storage, and distribution. The precinct benefits from strong occupier demand and very low vacancy rates, which supports rental uplift and long-term asset defensiveness.

Investment Potential:

Estimated Net Yield: ~6.8%

Estimated IRR (5-Year Hold): ~16–18%

Occupancy: ~90-100%

Exit Strategy: Institutional buyer or logistics REIT

Key Advantage: Premium location with superior access to Auckland’s logistics spine

Auckland – Boutique Hotel / Serviced Apartment Block

Asking Price: NZD 30 million

Asset Type: Mixed-Use | 62 apartments + 64 car parks (individually titled)

Land Size: ~3,600 m²

Built-Up Area: ~3,800 m²

Tenure: Freehold

Nearby Demand Drivers: Auckland education hub, transport links, suburban regeneration

Notes:

This is a rare, large-scale titled apartment block currently operated as a boutique hotel. Its dual-use capability (short stay, long stay, student housing, or staged sell-down of individual units) provides an unusual amount of flexibility for an income asset in Auckland. Avondale is undergoing a major regeneration supported by new transport links, higher-density zoning, and sustained tenant demand from students and young professionals.

The property is well positioned to benefit from the easing OCR cycle, with yield stability in the near term and potential capital uplift as financing conditions improve.

Investment Potential:

Estimated Net Yield: ~7.0 to 8.0%

Estimated IRR (5-Year Hold): ~17–19%

Occupancy: ~85-90%

Gross Sell-Down Scenario: ~NZD 40-50 million

Exit Strategy: Staged unit sell-down, PBSA conversion, or institutional sale once stabilised

Key Advantage: Multi-pathway asset offering yield, flexibility and exit optionality in a strengthening suburban corridor

Malaysia: Early-Stage Yield with AI-Adjacent Growth

Port Klang – Logistics and Distribution Facility

Asking Price: MYR 60 million

Asset Type: Industrial | Two-storey logistics and distribution facility

Land Size: ~3.76 acres

Built-Up Area: ~110,000 sq ft

Tenure: Leasehold with approximately 88 years remaining

Nearby Demand Drivers: Port Klang Free Zone, server-import staging, Klang Valley distribution corridor

Notes:

Situated within the country’s busiest maritime gateway, this asset benefits from consistent throughput linked to e-commerce, hardware imports, and regional distribution. Warehouse space in Pulau Indah remains tight, with rising interest from regional occupiers who view the Klang Valley as a cost-effective alternative to Singapore for bulk storage and processing.

Investment Potential:

Estimated Net Yield: ~7.0%

Estimated IRR (5-Year Hold): ~18%

Occupancy: ~85–90%

Exit Strategy: Institutional logistics REIT or cross-border portfolio roll-up

Key Advantage: Transit-oriented freehold property in KL’s densest workforce hub with adaptive reuse potential

Johor – Industrial Warehouse

Asking Price: MYR 100 million

Asset Type: Industrial | Single-storey warehouse with 29 dock levellers and 1,200 Amp power supply

Land Size: ~9.37 acres

Built-Up Area: ~176,400 sq ft

Tenure: Freehold

Nearby Demand Drivers: Senai Airport Logistics Hub, YTL–NVIDIA AI corridor, Johor–Singapore connectivity zone

Notes:

This is one of the larger freehold logistics platforms currently available in Johor’s northern industrial belt. With high-power capacity and an unusually deep land parcel, the property is suited for regional warehousing, hardware staging, or last-mile distribution supporting the emerging AI and cloud ecosystem in Johor. The surrounding area is undergoing a visible uplift in land values as hyperscaler investment accelerates.

Investment Potential:

Net Yield: ~7.0–7.8%

Estimated IRR (5-year hold): ~19-20%

Occupancy: ~90%

Exit Strategy: Institutional logistics fund or partial data-adjacent redevelopment

Key Advantage: Rare large freehold parcel with substantial power supply along Johor’s AI-related growth axis

Want to discuss any of these opportunities further? Reach out to our team directly:

Contact Information :

Petrus Yen - Managing Director

Petrus@fairhavenproperty.co.nz

Daarshan Kunasegaran

Daarshan.Kunasegaran@fairhavenproperty.co.nz

Disclaimer:

The property details, financial figures, and projections provided in this article are based on publicly available information and internal estimates. They are intended for informational purposes only and do not constitute financial advice or an offer to invest. Projections such as IRR and equity multiples are indicative only and subject to change based on market conditions, financing terms, and execution strategy. Interested parties should conduct independent due diligence and consult with a qualified advisor before making any investment decisions. Fairhaven Property Group accepts no liability for decisions made based on the information presented herein.